Jason Yeh is an ex-VC & the founder of Adamant, a group focused on making fundraising easier. Founders ❤️ binging his Fundraising Fieldnotes newsletter and podcast Funded before raising capital. Find Jason on Twitter: @jayyeh.

Although at the time of writing we may be experiencing a global slowdown in venture funding, the outlook isn’t all doom and gloom- the fourth-largest amount of funding on record occurred in Q1’22. Investors are still pouring capital into massive Seed & Series A deals, and record levels of investor dry powder from a peak in 2021 still remain.

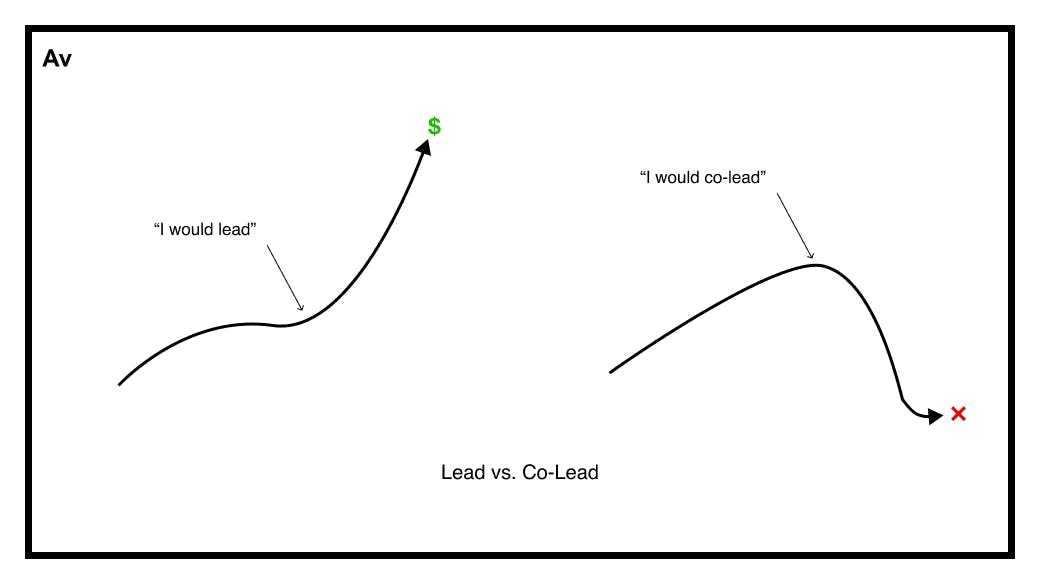

Recently, I’ve heard a common follow on question. What exactly is a lead investor, and what happens if a firm offers to co-lead instead? In my experience as a fundraising coach interacting with startup founders daily, the latter scenario is an increasingly common one that can often be a smoke signal that founders need to be wary of.

But first, what is a lead investor?

One of the most common misconceptions founders have is that lead investors have specific, binding responsibilities and obligations. In reality, as is the case with much of the vernacular around venture capital (what it means to “close a round,” for example) – there is no strict legal definition for what a lead investor is.

In broad strokes, a lead investor is the party that has the greatest conviction and support for the investment. What determines conviction? Most of the time, when multiple investors are involved, it’s simply whoever writes the largest check in the round. The lead investor also typically plays a key role in the negotiations of the overall agreement – valuing the company and helping set the valuation cap. If it’s a convertible note or SAFE and not a priced equity round, the lead investor will take on the dirty work of negotiating with the founder and asserting, for example, the valuation is $8M instead of $10M.

In the most traditional sense, a pure lead investor is 1) going to have at least 50% of the round and 2) will set the terms. Those are the two main things that happen with a traditional lead.

The proliferation of non-lead funds has made it challenging for some founders to find traditional leads, pushing them instead to try to pull together rounds without leads. These party rounds create a gray area of lead status, especially in seed / early financings that use notes or SAFEs. For example, for a $2M round, there can be three or four institutional investors each with check sizes of $500,000 to $750,000 investing in a note whose cap was set by the entrepreneur. In this scenario, no single investor has over 50% of the round and none would be considered a traditional lead. Those fundraises can be very long and drawn out as it can be challenging for a founder to galvanize momentum without a definitive “lead.” This is because founders will pitch investors who are “syndicate” or “follow-on” investors who either because of limited resources or willpower, don’t want to do the time-consuming diligence in determining whether a company is investable. Instead, they’ll ask who the lead is because they want to know which fund has committed to putting their reputational stamp on the deal, signaling that it’s worthy.

When faced with the prospect of trying to fill out a round without a true lead, I encourage founders to anoint a lead out of the current investors. In most cases, being able to point to a firm as the lead will positively impact the process. If asked details about there being a small check you can declare, “We discussed the cap with this fund and they agreed on the investment and the terms.”

What is a co-lead investor?

In my experience, the current trends around “co-leading” are not positive. Co-lead investors desire the recognition of being a lead without taking on the associated risks and responsibilities, while also wanting a larger allocation in the round than if they were just a follow-on investor. They don't want to take on all the work and commitment on their own. They will offer to co-lead and promise hefty checks but with a consequential caveat – only if the founder can find another firm who will co-lead alongside them.

To me, saying they will co-lead is a way for investors to shirk responsibilities and wait for others to validate the investment. These lukewarm investors are showing very little if any confidence in the deal with that conditional show of support. In my opinion, they are merely looking to ride on the coattails of other investors’ diligence and clout.

Inexperienced founders can be especially ecstatic the first time an investor agrees to invest. But if they’re only willing to co-lead, this excitement can be misguided. I caution founders that despite all the time and effort they’ve devoted to get an investor on board, the interest from a co-lead could be a red herring. Offering to co-lead without assisting founders in finding a complementary fund is actually a diluted signal of interest. Founders should treat these investors as non-leads until other action or behavior warrants otherwise. My primary worry in these situations is that founders will be misled and stop pushing ahead with other leads because they think they’ve found a real lead. Instead, a founder should stay the course and look for an investor with more conviction who is ready to actually “lead.”

When an investor says 'We’ll consider co-leading the deal,' it often actually means, 'We’re not that excited – go find somebody else'

Important qualifier: this is not to say that all co-lead investor scenarios are awful. Co-leading can be done with conviction. If a firm tells you they are willing to co-lead, ask yourself: are they leaning in, will they help you find another fund, are they thrilled to get the deal done? At the end of the day, an investor’s job is to aggressively pursue deals they like. It will be obvious when they are sincerely excited to be your partner.

There are many cases when two firms that traditionally lead deals on their own want to invest in the same deal and realize that the other also brings tremendous value to the company. In those situations they are willing to take less allocation to increase the value of the company. For example, Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital co-led the $35M Series B round for Tecton in 2020 and Sequoia co-led a $15M Series A round with Tiger Global in Toplyne earlier this year (2022). However, I haven’t been seeing as much of that in the earliest stages recently. Saying “we could co-lead” is thrown around- particularly at the pre-seed and seed stages of fundraising as an excuse or another way of saying “we’re not interested right now.”

There are many ways to close a round of financing between landing a traditional lead, a party round with valuations set by the founder, and even taking on co-leads. Whatever path you pursue, make sure you run a tight process till the end and sniff out false signals when they present themselves.