David Phelps is a 2x founder, a cocreator of ecodao and jokedao, and an investor in web3 projects through the angels collective he started, cowfund. Find him on Twitter at @divine_economy.

I.

I lost religion at some point in the middle of a conversation with a crush on AOL Instant Messenger. I was 15, and if you had asked me if I was in love with her, I would have denied it with a defensiveness bordering on desperation. But my face might have given me up when she asked me the question, “Do u believe in god?,” and I blanched.

For this was me at 15: attending Bible Study every week, teaching Sunday School, Altar boy in our old stone Church, an only child who had spent nights for years talking only to his mother, his cat, and God. And what did I know of her at 16? Psychedelic sympathies, like everyone I was becoming drawn to, a shared love of Odyssey and Oracle, an ability to articulate her desires that nobody else in our town of 17 churches seemed to share.

I mean that I admired her, and when I tried to strategically deflect the question back to her, I already knew what she would say. “No, u?” Well, “me neither,” I replied nonchalantly, trying to convince myself that my statement would relieve me of divine scrutiny for what I was saying. But in that moment of blasphemous typing, I had shed all that I knew about myself and the world and emerged as my true self: a lost and lovelorn teen, a counterculture striver, a sinner in the eyes of a deadbeat God. Some combination of a high-school crush, perpetually unsated desire to be cool, and extremely weak moral constitution made me understand that my two words would be worth the price of lifelong heresy.

In retrospect, though, it’s unlikely I ever would have stripped my Puritanism if not for the internet. My newfound apostasy found me bathed in the white-blue hues of the new ethereal—the AOL homepage—and facing the glow of this duller heaven, I could only blink.

Whoever or whatever I was becoming, the internet was making me in its image. The few keystrokes it took to fall from grace had long been preordained. God was dead, and AIM had killed him.

II.

The internet is one of the only religions in which we get to pretend we’re gods. Not good gods, exactly, but gods nonetheless.

The first point to make there is that the internet is fundamentally pantheistic. In this, the internet is really a public forum for a cultural imagination that has long worshiped conflicting deities at once: pastors and politicians, celebrities and cartoons. For those of us who have grown up online, we’ve lived in rickety versions of the metaverse for as long as we’ve been alive, raised biculturally across analog and digital worlds, forging separate-but-entangled identities on each. We’re the children of split custody ideologies—of socialism and Star Wars, poetry and code, the independence of working hard and the independence of hardly working.

On the internet, each of these figures and ideologies can come into contact under the jurisdiction of our moral—and moralizing—eyes, in a kind of Dante-like metaverse. It is a place where the occasionally richest man in the world can trade up his social capital by becoming, of all things, a dog-promoter. And it is a place where, whether you like it or not, you will be tempted into sentencing him morally for doing such a thing. You will like it or dislike it, but above all, you’ll perform that modern form of religious censure: the vibe-check.

The second is that the internet is a religion we get to shape and star in in real time. It’s not only characters and the celebrities playing them who interact with one another in performances straddling the lines of fiction and documentary. It’s us. Everyday, every one of us on the internet has a casino-shot of living out A Star is Born if we can just figure out the right permutation of 280 characters. If we’re good at the game, this game of becoming a God, we’ll do whatever it takes to will our best or worst selves into existence—enjoining our aspirational selves to be true so that we can give the people what we want to hear. The price to be original is, paradoxically, cliche.

On the internet, we can create our own religions, if we’re inclined, by creating ourselves in whatever image we like. Online, at least, we can tell ourselves that our bodies don’t keep the score: that we can present as we’d like to be seen, that we can form collective selves dissolving physical bounds, that we can move our bodies conscientiously, comfortable with all positions, never flinching when triggered by unremembered traumas. The narrative of who we are is ours to control, relinquish, and share.

But most importantly, we tell it about our God-self, a character who is a truer and falser us, an us we can perform more convincingly, with better lighting and skins. The ultimate myth we tell ourselves, then, is one about the role of myth itself: that we not only need to write our lives as storytellers but recite the lines as actors. That we wrote the lines ourselves. That they are somehow not banal. (We repeat them until they are.)

To live in this constant state of make-believe—not quite believing in our performances, nor in the script we enact, nor in the fact that we wrote it—is simply the state of being oneself online, of being the product of schizophrenic cultural wars, of growing up in the dueling shadows of God and Bowser. It is to live in a state in which we ourselves can play either but would, generally, prefer to play the former.

III.

I joked recently that crypto is the great religion of our time:

A simpler way to say that is that the religions operating as moral systems offer positive incentives for good behavior (prosperity here or hereafter) and negative ones for bad behavior (damnation for eternity). These are the core structuring devices of the Dante metaverse, though they’re articulated with annoying precision across religions. But the bigger point is that these incentives are only possible because they presume that our actions will be legible on a divine ledger—that there is an all-seeing eye to judge us in the first place for following its laws. God’s light doesn’t just give us vision; it traps us in his as well.

Or to put that another way: the most successful religions are, historically, gamified. A life battling moral temptation is, essentially, a choose-your-own-ending story, one that forces you to pick your team, complete quests, and try to win a prize (salvation, reincarnation, and the love of a Laura or Beatrice). Virtue doesn’t define the essence of our soul so much as it stands as an economic reward. Good karma must be earned, just as nirvana can only be attained by following the Noble Eightfold Path. To these moral incentives, Islam added a penalty as well: those who didn’t convert would be taxed or conscripted. The rules of the game here are the laws of the universe, as well as, occasionally, the laws of man.

What differentiates a religion from a game, then, except the spectrum between optionality and determinism, between make-believe and belief? It might make more sense to reverse the formulation, then—to say not only that successful religions are gamified but that successful games are religionized. The great games, from chess to Dungeons and Dragons, operate as minor religions with a cast of god-like avatars imbued with talismanic power, as well as endless narrative permutations from a few simple rules. Religions and games are, if you like, types of generative art that inscribe broadly archetypical characters within a set of limited scenarios in order to force big questions about how one acts and what that action means—whether it’s a reflection of one’s character or an opportunity to define it.

In that framework, it is not surprising to see infinitely reproducible information gain great value as a luxury when packaged as an NFT. You might say that the NFT isn’t real, that its value is the product of a mass delusion of consumers working within the same codes to attain status from one another, but people have said the same of God, religion, and games for centuries. NFTs are snarky, of course, deriving immense value from serving as fuck-yous to value both in their free distribution and frequent artlessness. They’re the totems of an internet-native religion with the same properties as all online viral content: contrarian, attention-seeking, community-cohering, altogether gorgeous trash.

If nothing else, the internet is good at allowing us to find others who will validate our banal interests, the sort we’d usually want to hide from our families and neighbors, and elevate them into objects of veneration. The internet is designed to help us trivialize worshipful affairs, just as it’s designed to help us worship trivial things. For better and for worse, it lets us design our own rules to the game.

IV.

Still, we might wonder whether those rules are dictated by historical imperatives, just as they’ve always been. An all-seeing God, an eye that gets us to comport with its expectations of moral decency, isn’t necessary in every religion, but is useful as an alibi for the surveillance state. Religions centered around single spirits—Hinduism, Christianity, Islam—arose as the product of imperial states that worked to centralize disparate regions around a shared authority; in a way, monotheism replaced polytheism at the same moment that empires replaced local states.

But what if those ancient pantheistic religions suggest a more intrinsic human need to believe in multiple authorities at once? And what if, beneath the surface, we’ve always been pantheistic? After all, Hinduism can’t exactly qualify as monotheistic, and even Christianity typically fragments into a Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. The fundamental polytheism of the internet might, in that sense, reflect our own promiscuous desires for the divine. At the very least, it might reflect the ways that the empires of the past 2000 years were possibly just a historical anomaly that are just dissolving, now, into online microcities and subcommunities.

Dust to dust; empire to DAO.

V.

In two quotes, we can see why the attention economy online has the power to decimate all other religions.

First, Katie Kadue, writing in n+1:

“What makes Twitter so axiomatically hellish? It’s a place where even the most well-intentioned attempts at intellectually honest conversation inevitably devolve into misunderstanding and mutual contempt, like the fruit that crumbles into ash in the devils’ mouths in book 10 of Paradise Lost. It amplifies our simultaneous interdependency and alienation, the overtaking of meaningful political life by the triviality of the social.”

And then David Hoffman, writing in Bankless:

“Now that we are on the periphery of the metaverse, it seems that Ethereum isn’t going to stop growing until it consumes all of our attention. If Ethereum doesn’t interest you yet, just wait. It’ll find a way. Something cool on Ethereum will be built, and that thing will be the subject matter of your homies’ group chat, or your family’s dinner table conversation.

Ethereum will accept everything that you put into it, and it will still have room for more.

The more attention you put towards Ethereum, the more financial rewards you tend to find, which makes “taking a break” have a significant amount of opportunity cost, and hence why this industry is generally a one-way street.

Those who enter do not leave.”

There is another term for this kind of religion—a casino. The slot-machine mechanics of Twitter and Ethereum both compel us into paying attention and lending our ears in a gambler’s hope of some return-on-attentiveness. They merge, perfectly, in NFTs, which are essentially Ethereum-disguised-as-jpegs that gain status both as images and objects of discussion almost exclusively on Twitter. Scrolling Twitter is the new form of prayer: an endless state of hoping for miracles by simply waiting around, alert.

If scrolling the internet dissolves us from material concern, well, then, that only makes the internet more powerful as a religion. Likewise, if the people we follow can have their status visibly denominated in the number of followers and Eth-value of their profile pic, well, then, that only makes it easier to know who to worship. And even amidst all the talk of decentralization, it’s the act of worship that helps us find our strongest communities. We get to create our own religions in real-time, in direct conjunction with the creators we worship.

Religion, like every other industry, now requires an interactive social layer to be successful.

VI.

So it is surely brute stupidity, if not a gambler’s self-justification, that I think we can use the internet to find paradise.

I want to go back, to a second, to that moment I lost faith in God because I thought the internet would give me a chance to appear to a crush on AIM as though I were, impossibly, cool. That’s the true story, which is why I’d like to tell a completely different one: that I had actually converted to a new faith many years before, when I stepped into the temples of Myst.

A groundbreaking slideshow of a game in 1993, Myst sacrificed storytelling to create a free and open world for players to walk around in, 3D-slide-by-3D-slide. Without either a story or a direction to orient oneself, Myst offered an initial template of digital boredom as religion: the meditative point was to lose oneself in the world, particularly in its clunky ancient temples. I never quite fell in love with Myst—I’m not sure anyone did—but I do remember rushing home from Church, with its rote obligations, so I could meander around Myst’s temples without any objective in the world. I was, in a way, finding a new religion, one in which my sole aim was to scroll and scroll and scroll until, in an epiphany, I would find something of inconsequential interest.

A game nearly without character or story, Myst might seem like the opposite of a religion in our earlier definition of characters-stuck-in-limited-scenarios. After all, to create a religion is, traditionally, to create a mythology of characters. And to create a mythology of characters is to deify our emotions—to freeze them as stone gods, universal archetypes shared by humanity that are abstracted from any of our own individual personality quirks.

Myst attempted to create a religious experience without gods most likely due to technical limitations. But there was probably a more pragmatic reason as well, as there is to so much New Age media: gods lose their power when they break their stony silence to start moving around like the rest of us fumbling human beings. When gods look too human, as they do in virtual worlds, they become too approachable to be divinities. Early Greek sculptors mastered the art of the contrapposto to suggest that their gods could lean their weight on one knee, could move. But what if we actually saw a god move? It would likely look like a kitsch puppet show.

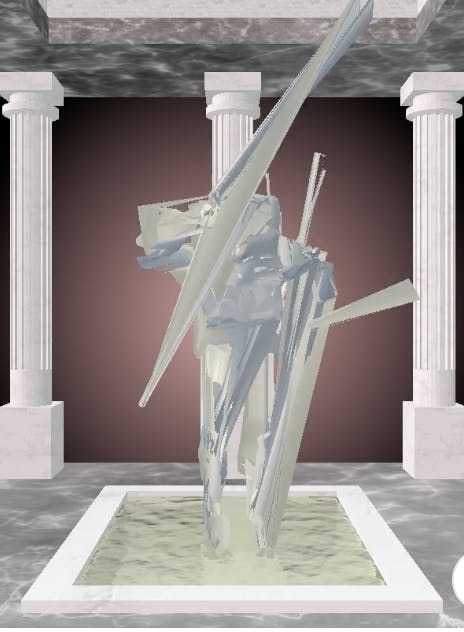

And yet, this is exactly the challenge the internet artist Godmin took on with her glitch art NFT collection, Heaven Computer. Each NFT returns us to a boxy Myst-like temple of mid-90s 3D, this time with the gods in the center of the room: janky, half-formed gods that appear to move as though they were short-circuiting, their own bodies occasionally rupturing in pixels towards us at the boundary of figuration and abstraction, either due to the power of their divine incandescence or, more likely, the limitations of glitchy software. Like a Titan stuck in a Python loop, each is programmed to repeat a gesture for infinity that expresses a universal emotion in the vernacular of a flippant teenager: teasing throat-cutting threats, giddy cheerleader jumps, or a hand sassily forming an L to tell you, the would-be buyer, that you’re a total loser.

Just as the broken-record visuals are too abstract to seem believable, the actions are too believable for the gods to have abstract power: they’re too rooted in a particular historical moment, too relatable, both too human and too digital, to make us think we’re seeing anything other than a blasphemous copy of a copy of a copy of a divinity. And yet, there is something touching and beautiful in their failed quest to take shape, complete an action, or convince us they’re anything but a 90s relic—like all of us, these computer gods are desperately simulating what it might be like to be human. On open calls with Godmin, rapturous devotees of the project often reiterate the connections they feel with the NFTs as echoes of lost family and friends.

Godmin reminds me, in a way, of another artist: Sara Issakharian, a Persian Jewish painter based in the US who often depicts scenes from mythology, the Bible, and Donald Duck cartoons in scribbles and erasures. The subject for both artists is, in a way, the collapse of religion to a single plane where divinities from different universes all begin to intersect in a kind of trance that’s half-remembered, half-believed. In that sense, the subject is something like the internet itself: a site that flattens history and beliefs to create a self-conscious, pantheistic terrain of intersecting subcommunities, of lost and wandering gods.

It would have been tempting a few years ago to think that the internet would simply kill religion because it was a force of unbridled capitalism and irony alike, too performative and unserious to broker any kind of serious belief. But wonderful works like Heaven Computer—as well as much darker ones like incel memes—are a reminder that unserious games can be very serious belief systems. The internet, in other words, is not just a way to raze, flatten, and cross-pollinate centuries of historical religion-building. It is also, in its own way, a religion itself.

To worship at the internet’s altar of boredom and outrage—the state of all of Heaven Computer’s gods—is desperate business, of course. But what if it could also be a Myst-like meditation? What would the internet look like if we stopped seeing ourselves in its image, and we started creating it in ours?

What if we realized not only that the internet is an inevitable religion, but the first one that humans have had say over en masse—the first time we’ve gotten not just to choose but to define our own system of belief?

***

Special thanks to Tina He and Lani Trock.

And usual disclosure: I have works by both Godmin and Issakharian.

–

This article originally appeared on Three quarks – deep dives into crypto and web3: what does the past of tech, culture, and economics tell us about their future?