David Phelps is a 2x founder, a cocreator of ecodao and jokedao, and an investor in web3 projects through the angels collective he started, cowfund. Find him on Twitter at @divine_economy.

I guess I should start with this confession here in the church of business strategy: I’ve long been a skeptic of network effects, a fact I mostly attributed to my mother, who raised me with a parsimonious skepticism of prices generally. Entering the high-end entrances of the mall—your Ralph Laurens and, if necessary, JCPenney—she would teach me to flip price tags ruthlessly on each necktie and pair of khakis we stormed past, as if to expose the fundamental con game that was item-pricing. The reason we were storming so quickly past these Sunday School attires—”crap,” as my mother would say—was because we were in a hurry, of course, to get to Marshalls.

Marshalls was a promised land of pricing, I learned, because while its clothes might be a size too large and a season out of date, its bargain-basement fees meant it could be trusted. And what else mattered? So, as an adult, I would switch indiscriminately between real estate platforms and ride-sharing apps with little regard for their supposed network effects. I wanted the lowest price.

And now that we can look at these markets, many of them still fighting decades-long pricing wars against their competitors, we should ask: was I right?

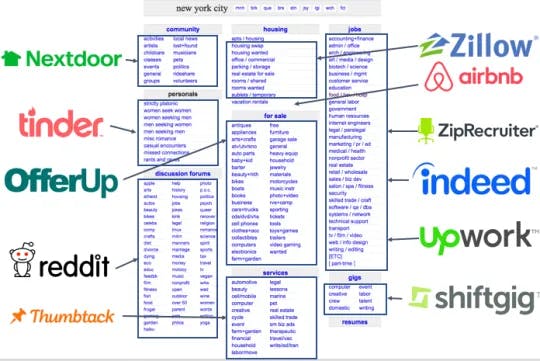

It might be helpful, to start, to distinguish between two types of network effects—those that lead to winner-take-all successes and those that don’t. For example, take the famous diagram portraying the Unbundling of Craigslist, courtesy of a16z.

Looking at this graphic, my friend Mac Reddin made a seemingly obvious point that articles, including my own, tend to miss: the image is a combination of semi-failures and companies battling competitors for market share, even frequently against Craigslist itself, which continues to rake in at least half a billion dollars a year. Craigslist wasn’t really unbundled into verticalized platforms. Instead, it was forced to compete on an increasingly splintered playing field with a multitude of half-satisfactory options. Even despite itself, what the diagram really shows us is not the victors of the past decade, but how rare winner-take-all marketplaces truly are.

So if we want to understand why network effects often fail to lead to marketplace monopolies, we should start by considering the Thumbtacks against the Taskrabbits, the Tinders against the Bumbles, and the Upworks against the Fiverrs, all in relentless competition against mirror-image services. These services all have network effects in the traditional sense: by adding more participants to their marketplace, they create a better experience for their user. So why do they fail to claim the market? And why do others, like Facebook and TikTok and perhaps even Airbnb, succeed?

There are likely a few explanations, including the vagaries of luck and capitalization, as well as how broadly we define given markets. For example, if we define markets broadly enough, Facebook can stop appearing as a winner-takes-all success and start to look like it’s competing with Twitter or even Netflix for our attention and time.

My own explanation, though, is that it's a question of fungibility. To have a truly winner-takes-all marketplace requires non-fungible supply and, especially, demand.

For the sake of visual simplicity, we’ll demarcate “fungible” as the twins from the Shining, fairly replaceable clones of one another, and “non-fungible” as Michigan J. Frog, the irreplaceable emcee of that cinema classic, One Froggy Evening.

So how do we fill this in? And what does it mean?

Non-fungibility = winner-takes-all

Let’s start with some twins: Coinbase and Kraken, if you like, or Uber and Lyft. The buyers and sellers on the exchanges are interchangeable for users, as are the taxi drivers and riders. Supply and demand in both cases is fungible: it doesn’t matter who you’re trading with, just that there is someone to complete the transaction. This interchangeability is, in fact, part of what allows these companies to have network effects in the first place by easily aggregating a mass of potential transactors within otherwise limited criteria (price, location).

But at a certain point, the marginal benefit of an additional user to the platform becomes negligible. Uber needs a critical mass of drivers on the streets to satisfy riders’ demands in a short amount of time, just as Coinbase needs a critical mass of sellers to satisfy buyers’ demands. Past that critical mass, however, the benefits to users are few because new supply can only replicate the old—the n+1th taxi or doge seller looks just like the nth taxi or doge seller—and users will be more incentivized to care about price. Ultimately that fungibility means that users don't have great reason to be loyal to a given platform when other, potentially cheaper options are also available by competitors.

Content, however, is not fungible; it is unique not only to a content-creator but to the medium they use. Marketplaces that become content marketplaces win the market because it is impossible to get their individuated content anywhere else.

For example, look at Twitter and TikTok, true singing frogs. Twitter and TikTok stand as particularly power and irreplicable platforms because they create new types of expression unique to their medium—in both cases, ironic, referential, Lego-like pieces of dialogue that could be connected and reconnected to thousands of others with shifting meaning, sounding nothing like the way people speak, talk, or write in other formats. In other words, they generate content that’s entirely non-fungible in an easy interplay between supply and demand, between creating, consuming, and replaying. The n+1th user on Twitter or TikTok adds just as much value as the nth user because they are not interchangeable with their predecessors.

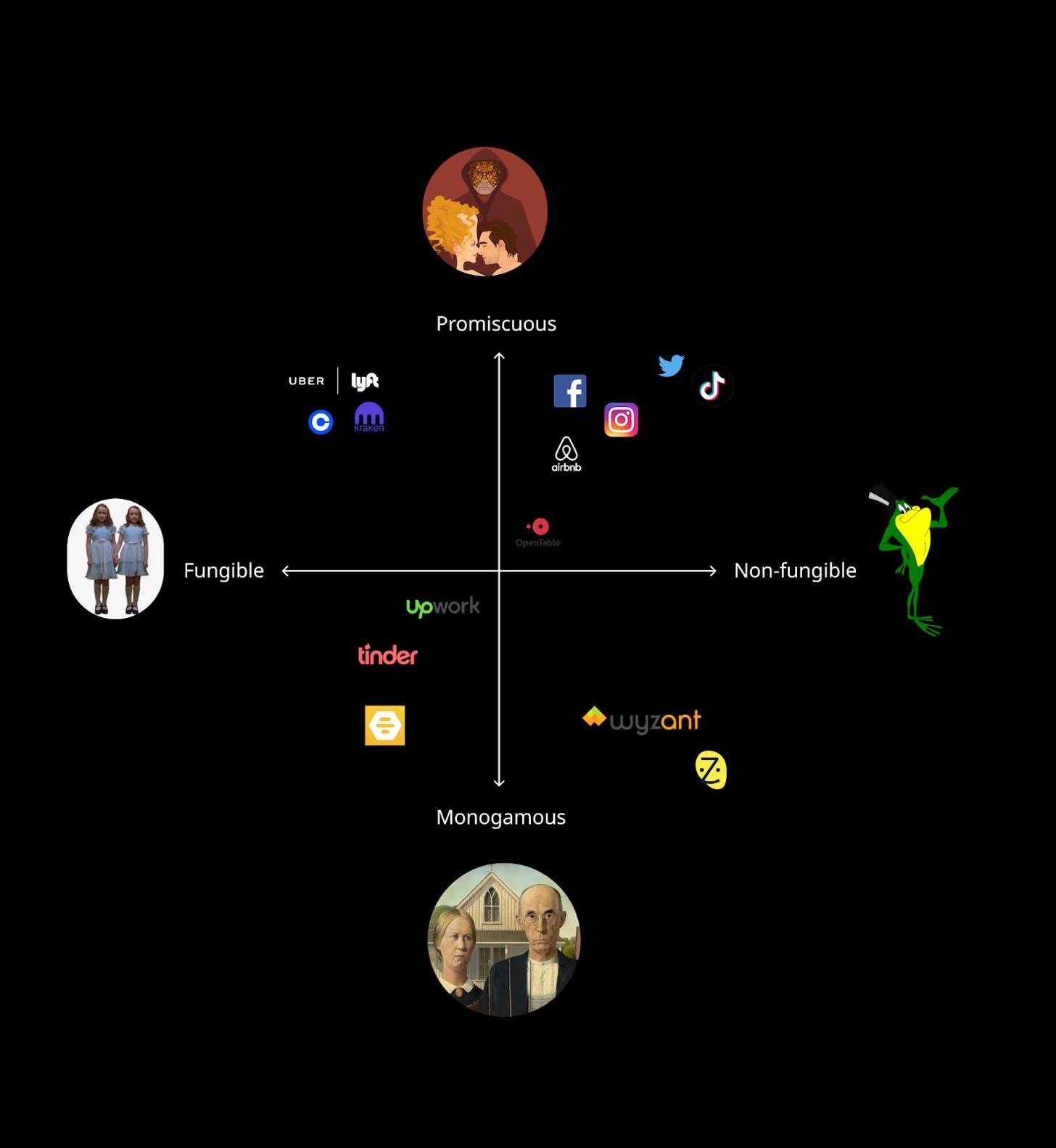

We can start to fill in our chart to show whether marketplaces will be winner-takes-all—whether, that is, they offer non-fungible content.

One of the unsettling implications of this argument, however, is that in the eyes of human beings, other humans can be more fungible than houses. If the spectrum above is correct, the dating apps compete for market share in the far wilds of fungibility while Airbnb mostly controls a non-fungible market. In other words, dating apps are not content platforms: everyone is fairly interchangeable for a user who's browsing quickly, and if certain options aren't available on a given platform, it won't impact their desire to use the platform as a whole. (They don’t care if the n+1th option is there or not.) A house rental app like Airbnb, however, is a content platform: users would be hesitant to use a competitor that might be missing a specific option. (They care very much whether the n+1th option is there or not.) In fact, it's notable that Airbnb vanquished its competitors when they sent photographers to make the homes look nice in 2010. They realized, in effect, that they were a media marketplace and that privileging the content would be the key to success. They were right.

Still, fungibility is a spectrum, and as David Wei pointed out to me, Airbnb continues to face tough competition from VRBO, likely because if users really do want to make sure they’re not missing out on the n+1th option, they’ll want to check every option on every platform. Another way of seeing the fungibility spectrum, then, is as a measure of how difficult it is to transfer service from one platform to another. As Max Glassman put it in reviewing this argument, “it's all about switching costs… It would be difficult to find our favorite leaders' thoughts in 280 characters elsewhere.” This is another way of defining fungibility, but one that’s less vindicating of Airbnb. With rentals, it’s a pain-but-not-prohibitive to shift inventory from one platform to another, just as it’s a pain-but-not-prohibitive for users to shift through endless options on multiple platforms to find the option they want. Airbnb is far more monopolistic than Uber because its content is much more non-fungible, but it’s unlikely to be a perfect monopoly.

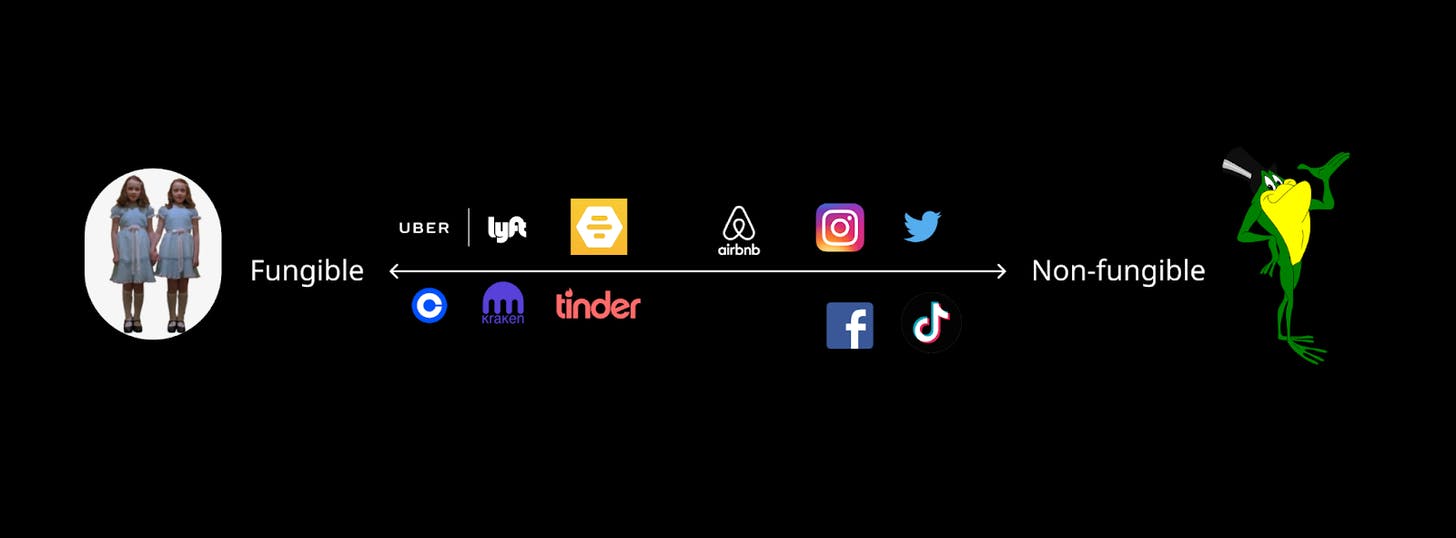

So our spectrum ultimately looks like this.

The Promised Land of the Singing Frog

That leaves one last, crucial question about how to create a non-fungible marketplace. What gets us to the promised land of the singing frog? When I proposed this argument to the electric intellectual community at The Generalist, I got a couple very sharp responses. Jim Shook pointed out the power of reviews—“the more reviews something has, the more pricing power the supplier has”—while Colin Gaffney cited Benedict Evans’ case for the scaling power of proprietary data that platforms collect. “When self-driving cars become normalized, would anyone want to use the 2nd best algorithm?” he asked. “There is an apparent winner-takes-all effect here based on a data moat.”

These, too, are ways of reflecting on the underlying non-fungibility of the product or service being offered. Reviews represent non-fungibility on the demand side—they help distinguish offerings, but they also only are useful if the offerings are already distinguished. Reviews for a Coinbase trader are unnecessary, as are reviews for most drivers, but for rentals they are crucial. Likewise, data moats represent non-fungibility on the supply side—they help make targeted recommendations to users, but these only matter if the users themselves are non-fungible and prone to different preferences within the platform. Uber and Tinder don't really need a lot of data on user preference because they just need to deliver whatever is local; Twitter and Facebook benefit greatly from user data to customize accordingly since the supply of content (and ads) is nearly unlimited.

Sarah Tavel identified exactly this point in her seminal “Hierarchy of Marketplaces” from last year. “Homogeneity of buyer need,” she points out, kills the possibilities for a winner-takes-all marketplace. “Each buyer on Airbnb has a different preference, which means that each additional unit of supply creates more marginal happiness for buyers.” The non-fungibility of buyers in their preferences turns out to correlate to the non-fungibility of the supply—a wider spectrum of tastes requires a wider spectrum of options to fulfill them.

Tavel’s point that marketplaces with differentiated options lead to greater possibilities of happiness presumes, of course, that the marketplace can fulfill some great measure of happiness in the first place. In her own classic axiom, “the marketplace that wins is the marketplace that figures out how to make their buyers and sellers meaningfully happier than any substitute.” Marketplaces that eliminate pain points—like Coinbase or Uber—can make users meaningfully happier than the incumbent hackable exchange and medallion cabs, but they struggle to make users meaningfully happier than their own clones, the Krakens and the Lyfts. Marketplaces that create entire new experiences for happiness, however, like Airbnb and Twitter and TikTok, can make users happier than any substitute simply because they can’t be cloned. These platforms aren’t merely letting users fix pain points with an interchangeable solution but offering up content that itself will give their lives added meeting. That means they’ll need to appeal to a broader variety of preference—and will need to have a non-fungible supply of options to meet it.

We return to my mother’s insistence on the Marshalls of the world over the JCPenneys. In another classic formulation, Tavel writes that ““[10x product] and save people money” is the key formula for marketplace success. Uber could be 10x better than medallion cabs and save people money; in comparison to Lyft, however, it can only save people money. When marketplaces can’t be 10x better than their own clones, users will inevitably fall back on pricing alone for comparison—foreclosing any possibility of winner-takes-all. For my mom, stores were essentially clones with the same possibilities of happiness, so price became the crucial variable to distinguish them. Non-fungibility of supply and demand earns marketplaces the entirety of market share because only they and they alone can meet the vagaries of individual taste.

Let’s Get Fungy

This may seem like a counterintuitive argument because in many ways the non-fungible marketplaces are the ones that have really failed. Uber and Coinbase are, after all, behemoths and by most definitions, wildly successful companies; Zocdoc and Wyzant, which thrive off the altogether non-fungible relationships that individuals build with doctors and tutors, are not. Bill Gurley, however, has given another framework for this phenomenon: promiscuous vs monogamous. Promiscuous marketplaces like OpenTable are ones that users need to keep returning to for more options; monogamous marketplaces like Zocdoc and Wyzant are ones that users often try once to find a long term option whom they’ll quickly take off-platform. That means, in other words, that monogamous marketplaces tend to be relationship based, and that Tinder, incredibly, is something of a monogamous marketplace itself.

To the twins and Michigan J. Frog, we add some new friends: a promiscuous Tom Cruise and the dolefully anything-but-promiscuous couple from American Gothic.

Fascinatingly, we notice that fungibility creates very good businesses on both the promiscuous and monogamous side of the spectrum. That makes sense for two reasons. First, as we noted above, fungibility makes it easy to build a giant marketplace of interchangeable options in the first place. Second, it’s difficult to be completely fungible and completely monogamous—if a product or service is completely replaceable, then it’s unlikely a buyer would want to enter into an exclusive long-term relationship with a particular option. Dating apps and worker apps like Upwork and Taskrabbit come close to fulfilling both criteria, but full monogamy is rare: it’s normal for users to return to the platforms after extended periods of time to try new options.

Non-fungible markets, however, create both the very best and the very worst companies, depending whether they’re promiscuous or monogamous. Monogamous, non-fungible marketplaces are terrible business propositions: users will find a specific option that they like and leave the platform to continue with that individual forever. Promiscuous, non-fungible marketplaces, however, are the best business propositions: users will need to continue returning to the platform both to fulfill their individual taste (non-fungibility) as well as to find more options that match their preferences as well (promiscuous). These are, in many ways, the greatest marketplaces.

Finally, one last note. It’s entirely possible that this entire argument is bosh, a snapshot from a moment when well-capitalized legacy platforms like Uber and Lyft appeared to be stuck in an eternally duopolistic battle. It’s entirely possible that eventually one will run out of money and the other will win; or it’s possible that neither will be able to monetize effectively, and both will go out of business (though this seems especially unlikely). It’s possible that this argument questions the orthodoxy of the past decade only to propose its own arguments from a half-written history.

If it is right, though, it should make us rethink our conceptions of moats generally. In his wonderful 7 Powers, Hamilton Helmer writes that Network Effects “are frequently characterized by a tipping point: once a single firm achieves a certain degree of leadership, then the other firms just throw in the towel.” The argument above counters that point—in fact, winner-take-all markets are exceedingly rare.

Helmer’s framework of other “powers” that give companies defensibility is especially helpful here because, as it turns out, “switching costs” and “cornered resources” may not be separate categories from network effects, but the crucial determinants of non-fungibility that can make items in a marketplace unique—and can make network effects especially strong. After a few decades in which giant aggregators have become the dominant marketplaces while original media companies often seem relatively small, this framework is a reminder that the most successful marketplaces are always media marketplaces—for social media, for beautiful images of houses, for whatever helps one person’s unique, non-fungible taste somehow match with another’s. The internet itself becomes the greatest media marketplace here by allowing us to connect across the globe to others who share our own idiosyncrasies, even as it teases us that, inevitably, there’s always an n+1th option out there, just waiting, if only we can keep up the search.

A particularly special thank you to The Generalist community, which offered ample input on this piece. If you haven’t, join The Generalist. It’s life-changing if you like to play the competitive game of thinking.

–

This article originally appeared on Three quarks – deep dives into crypto and web3: what does the past of tech, culture, and economics tell us about their future?